When we think of the term “psychologist” a variety of adjectives usually come to mind – with words such as brilliant, calm, insightful, professional, concerned and helpful likely among them. And when we consider those psychologists who performed groundbreaking research, who contributed most significantly to the human lifestyle and who initiated major positive changes in society, our admiration perhaps grows even more. But things are not always as they seem. They say there is a fine line between genius and insanity. For a few of the most influential men in the field of psychology, the saying probably rings true.

When we think of the term “psychologist” a variety of adjectives usually come to mind – with words such as brilliant, calm, insightful, professional, concerned and helpful likely among them. And when we consider those psychologists who performed groundbreaking research, who contributed most significantly to the human lifestyle and who initiated major positive changes in society, our admiration perhaps grows even more. But things are not always as they seem. They say there is a fine line between genius and insanity. For a few of the most influential men in the field of psychology, the saying probably rings true.

Harry Harlow

What he contributed:

[showmyads] Harry Harlow’s studies demonstrated the importance of care-giving and companionship in social and cognitive development. His research made immense contributions toward the understanding of concepts such as learning, affection, interpersonal relationships and motivation, breaking new ground in general and child psychology. Harlow’s work sparked significant changes in the manner in which adoption agencies, orphanages, social services groups and child care providers approached the care of children. “Thanks in part to Harlow, doctors now know to place a newborn directly on its mother’s belly after birth. Also thanks in part to Harlow, workers in orphanages know it’s not enough to prop a bottle; the foundling must be held and rocked, see and smile” (Slater, 2004).

John P. Gluck (2007) reported:

During his lifetime, Harlow published approximately 325 articles and books and received virtually every available prize for scientific achievement, including the coveted Gold Medal from the American Psychological Association, in 1973, and membership in the American Philosophical Association. In 1951, he was the first psychologist to be elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences. He received the National Medal of Science from Lyndon Johnson in 1967, the Kittay Award from the Psychiatric profession in 1975, and honorable mention from the Nobel Committee in 1973.

By torturing baby monkeys. Harlow himself referred to some of the tools used in his research as iron maidens (lifeless metallic surrogate mothers covered in spikes and blasting out cold air), the rape rack (a forced copulation device) and the pits of despair (wedge-shaped stainless steel isolation chambers used to house infant monkeys for up to years at a time).

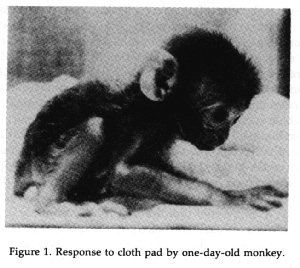

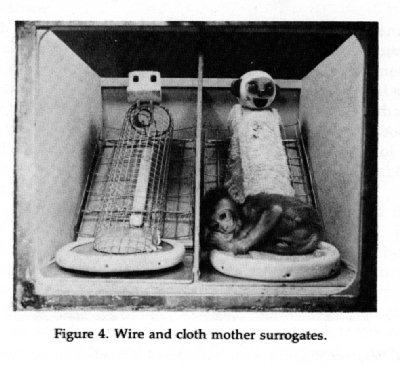

In The Wire Mother Experiment (one in a series of similar experiments between 1957-1963), Harlow removed baby rhesus macaque monkeys from their natural mothers and left them with a choice to be “raised” by one of two artificial mothers – a mother made out of warm, soft terrycloth that provided no food or a mother made from cold, hard wire that dispensed milk. The results of the study showed that the young moneys spent considerably more time with the cloth mother than its milk-giving wire counterpart, highlighting the extreme importance of contact comfort in child rearing and development (Harlow, 1958).

In The Wire Mother Experiment (one in a series of similar experiments between 1957-1963), Harlow removed baby rhesus macaque monkeys from their natural mothers and left them with a choice to be “raised” by one of two artificial mothers – a mother made out of warm, soft terrycloth that provided no food or a mother made from cold, hard wire that dispensed milk. The results of the study showed that the young moneys spent considerably more time with the cloth mother than its milk-giving wire counterpart, highlighting the extreme importance of contact comfort in child rearing and development (Harlow, 1958).

During the infamous Pit of Despair experiments, Harlow placed monkeys between three months and three years old in the previously mentioned steel isolation chambers, after they had already bonded with their mothers for up to ten weeks. A few days later, the baby monkeys had stopped moving about and remained huddled in a corner. Those left in the isolation chambers for thirty days suffered enormous mental damage. Those left for months or years showed all the signs of full blown depression. They did not play, barely moved, mutilated themselves, had no sexual relations and were badly bullied. Two of the formerly isolated monkeys refused to eat and starved themselves to death (Blum, 2002).

Harry Harlow’s experiments were shockingly cruel and often left the poor animals completely devastated (Gluck, 2007). But Harlow remained utterly unmoved. “The only thing I care about is whether a monkey will turn out a property I can publish,” he said. “I don’t have any love for them. I never have. I don’t really like animals. I despise cats. I hate dogs. How could you love monkeys?” (Slater, 2004).

How did Harlow’s associates in the scientific community feel about the controversial techniques used in his experiments? Former student and colleague Gene Sackett suggested that “these types of experiments, and the graphic language that was used to describe them, provided much of the tinder for the ignition of the animal rights protection movement” (Gluck, 2007). According to Blum (1994), world renowned researcher and former student William Mason exclaimed:

He kept this going to the point where it was clear to many people that the work was really violating ordinary sensibilities, that anybody with respect for life or people would find this offensive. It’s as if he sat down and said, ‘I’m only going to be around another ten years. What I’d like to do, then, is leave a great big mess behind. If that was his aim, he did a perfect job” (pg 96).

References

Blum, D., (1994). The Monkey Wars. United Kingdom: Oxford University Press

Blum, D., (2002). Love at goon park: Harry harlow and the science of affection. Cambridge, MA: Perseus Publishing.

Gluck, J. P., (2007). Harry f. harlow and animal research: reflection on the ethical paradox. Ethics & Behavior, 7(2), 149-161. Retrieved on February 14, 2012 from http://www.rw.ttu.edu/ethics/pdf’s/O5%20.pdf

Harlow, H. F., (1958). The nature of love. American Psychologist, 13, 573-685. Retrieved on February 14, 2012 from http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/Harlow/love.htm

Slater, L., (2004, March 21). Monkey love: Harry harlow’s classic primate experiments suggest that to understand the human heart you must be willing to break it. The Boston Globe. Retrieved on February 14, 2012 from http://www.boston.com/news/globe/ideas/articles/2004/03/21/monkey_love/